The German Blücher and the Battle of Drøbak Sound

Posted by MegaHobby.com on Jul 29th 2016

Per the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was limited in the number of battleships and cruisers that they could have in their military after World War I – and those they were allowed had significant restrictions with regards to their size, strength and capabilities. But after the rise of the Nazi Party in the mid-1930s and the formal rejection of the Treaty, the German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, began work on the Admiral Hipper class, a group of cruisers that would help lead ships into battle in their quest for European dominance. This would be the start of their return to military power in the region.

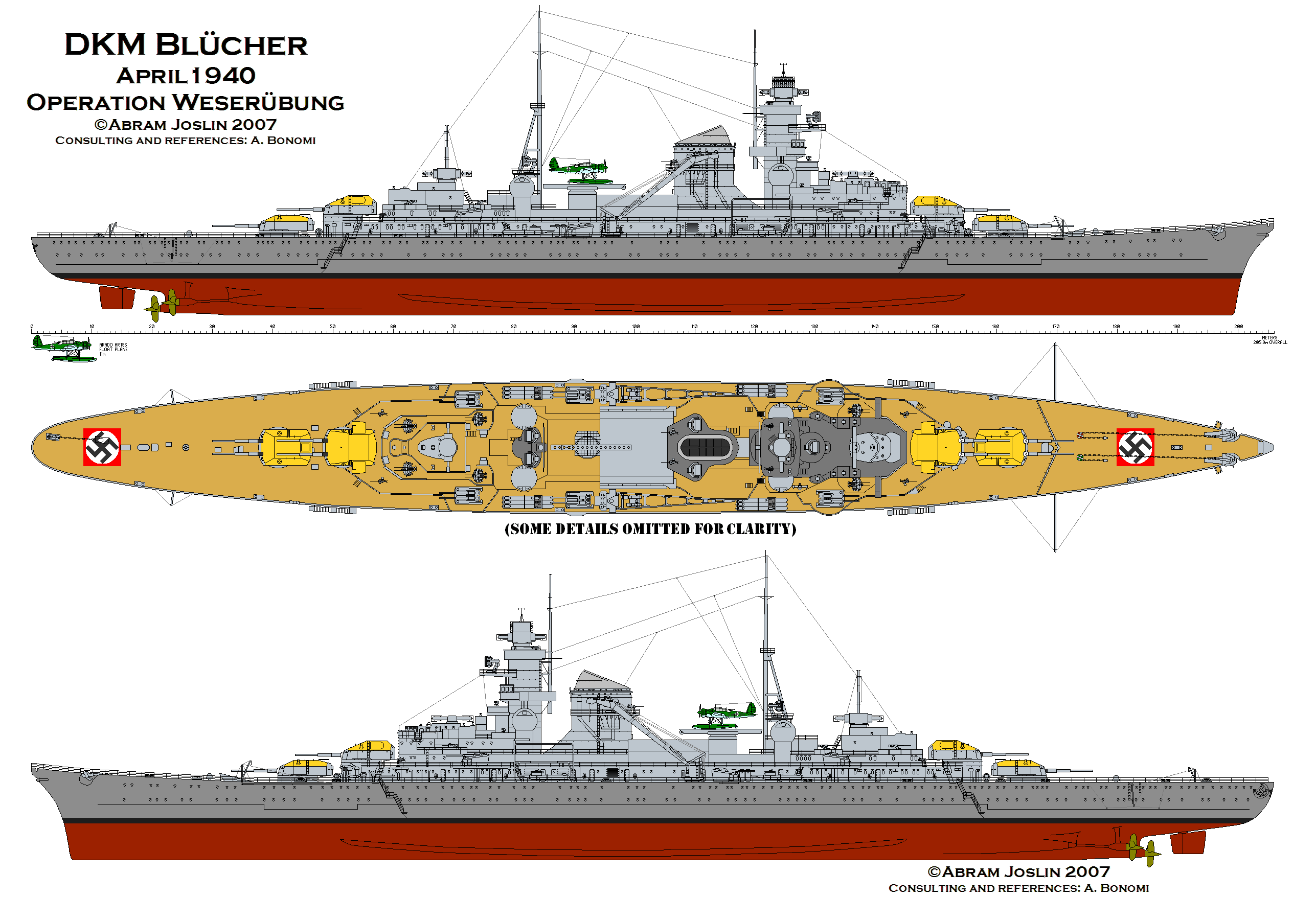

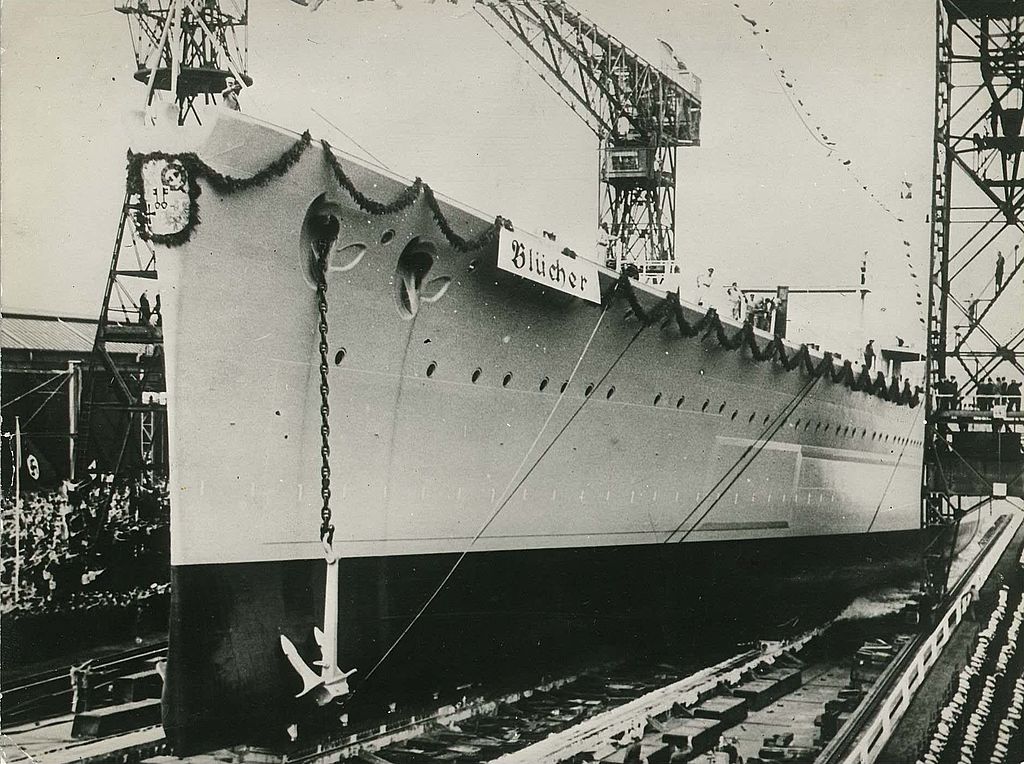

Just a few years after the first ship, the Admiral Hipper, they began work on their next biggest ship, one of the most powerful cruisers of its time. Laid down in August 1936 and launched in 1937, this ship was over 660 feet long, 70 feet wide, and carried enough weapons to conquer a port city. She carried two 53.3 cm torpedo launchers at the rear and four more on the main deck. She had eight 20.3 cm SK L/60 mounted guns, an anti-aircraft battery with 32 mounted guns, space for three Arado Ar 196 seaplanes, a catapult, and room for over 1,300 sailors. The German cruiser had three sets of steam turbines, whose steam was created with 12 ultra-high pressure oil-fired boilers. With this power she could cruise as fast as 32 knots. She was named the Blücher, in honor of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, the Prussian field general who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo.

After going through dozens of training exercises in the late 1930s, the Germans finally declared her fit for battle, and she was immediately designated the flagship in Operation Weserubung, whose mission was to capture Oslo, the capital of Norway. The ship was filled with over 1,000 men, including hundreds from the 163rd infantry division, who would disembark upon arrival in Oslo to take the city on foot. She was accompanied by the Lutzow, a fellow heavy cruiser, the light cruiser Emden, and multiple escort ships.

As they passed through the Drøbak Narrows on the night of April 8, 1940, the narrowest body of water en route to Oslo, the seas remained oddly quiet as Norwegian commander Birger Eriksen stood watch at the nearby Oscarsborg Fortress. Responsible for keeping a lookout for enemy ships approaching, Eriksen and his men were relying on manual methods of detection – the fortress was staffed mainly by recent recruits who were undertrained and slow to carry out their duties. Their underwater naval mine barrier was supposed to be installed days earlier, but had gotten delayed, and was scheduled to be put into place in the upcoming day or two.

But as the German flotilla passed through, Eriksen got notice from Pol III, a Norwegian patrol boat, that there were unidentified ships in the vicinity. The patrol boat was quickly hit and sunk by a German torpedo, but not before Eriksen could sound the alarm and alert the entire fortress. He immediately ordered that all lighthouses and navigation lights be extinguished, making the fortress nearly invisible. The German ships continued to sail by, under strict orders not to fire on anyone unless they were fired upon. The Norwegians, however, were not necessarily under the same orders.

The commander had not received clear orders, making him unaware who was approaching – Allied or German ships. Officially, Norway was neutral in the war, even though it was assumed that the government would side with the Allied Forces if push came to shove. But when he realized how many ships were in the flotilla, which had now come to a halt just outside the fortress, he ordered the lead ship to be fired upon. When his men questioned his judgment, he uttered: “Either I will be decorated or I will be court martialed. Fire!”

The first few shots from the fortress’ mounted guns missed, but alerted the Germans that they were no longer moving in stealth. At 4:20 in the morning, as the Blücher and her followers proceeded deeper into the fjord, in order to reach Oslo by dawn, the fortress’ searchlights hit the side of the ship, suddenly making her visible to all of the Norwegian forces. The Blücher, who was surprisingly close to land, was immediately fired upon from very close range by the 28 cm guns of Oscarsborg Fortress, with two shells making contact.

The initial shot hit Blücher on her port side above the bridge, knocking the main range finder out of alignment. The second shell, however, entered the aircraft hangar, where the seaplanes were housed, and started a fire. As the fire spread, it hit a collection of explosives being kept for the raid on Oslo, and detonated, blowing a huge hole in the armor deck. Despite being hit multiple times, the German forces still were unable to determine from where the gunfire was originating.

A few minutes later, two Norwegian torpedoes made contact with the Blücher, hitting her in the boiler room located just under the funnel and knocking out all but one of the boilers. Despite the ship losing most of her power, she trudged on and passed through the Norwegian firing zone, as the men of Oscarsborg continued shelling the remaining German ships.

But even after she was wounded and no longer under attack, the sailors on board the Blücher were struggling to rectify the situation. The fire was roaring out of control, the ship was unable to move very quickly, and hope seemed to ferociously drain away from the German soldiers. At 4:50, Blücher dropped her anchors, in a sign of near-defeat. German soldiers suddenly burst out in song, singing “Deutschland Deutschland uber alles.” The Norwegians on nearby land heard this and finally, for the first time in nearly an hour of battle, realized who they were fighting.

At this point, Blücher was already listing nearly 20 degrees and en route to a new home at the bottom of the sea. The raging fire spread to the ship’s ammunition magazine storage room, exploding violently and tearing a hole in the side of the ship, while also igniting the ship’s fuel stores. Everyone was ordered to abandon ship, as the Blücher rolled over onto her port side and, bow first, sank into the ocean, leaving hundreds of sailors swimming for their lives near the island of Askholmen. Oil leaked out of the Blücher as she fell, igniting from the existing fire and further killing hundreds more soldiers.

Despite the remaining German forces arriving the next morning in Oslo and quickly capturing the city, the slight delay that was incurred when Eriksen’s men barraged the German flotilla gave them enough time to notify the government of the impending attack, allowing members of the government, including the royal family, to flee Oslo and exile to the United Kingdom, before Norway officially surrendered a few months later.

The battle of Drøbak Sound was one of the stranger ones of World War II. The Blücher was filled with troops specifically designed to storm the government buildings and capture the king, the Norwegian cabinet and parliament, and the nation’s gold reserves. But the brand new ship was stopped in its tracks by a fortress that was over 100 years old, armed with weapons that had been stationed there for nearly half a century, by raw soldiers who had just completed their initial military training.

Blücher remains at the bottom of Drøbak Narrows today, laying 210 feet below the surface. The ship’s screws were removed in 1953, and despite several proposals to raise the ship, none of been carried out. With nearly 100,000 cubic feet of oil on board when she left Germany, she began expelling oil into the sea the second she was sunk. In the early 1990s the rate of oil expulsion increased to nearly 13 gallons per day, forcing the Norwegian government to send divers to the wreck to remove as much as they could.

In October 1994, Rockwater AS, along with deep sea divers, set out on expedition to the Blücher, drilled holes in 133 of her fuel tanks and removed 1,000 tons of oil. The remaining 47 fuel bunkers were unreachable and still eject trace amounts of oil to this day. But the oil that was removed was cleaned and sold for Norway’s benefit.

But while they were underwater, Norway didn’t just grab the oil that was hurting their environment. As a trophy, they also removed the Blücher’s anchor, and placed it just onshore for all to see. They also removed one of the two Arado 196 aircraft, and placed it in their Flyhistorisk Museum in Stavanger, Norway, where its frame still stands today. The two mementos remain in Norway, where they serve as a reminder of the dark times of world history, but also the courageous defense that hundreds of young soldiers mounted for their beloved country over 75 years ago.